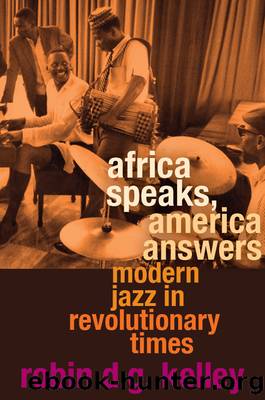

Africa Speaks, America Answers by Robin D. G. Kelley

Author:Robin D. G. Kelley [Kelley, Robin D. G.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780674046245

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: Harvard

Published: 2012-02-27T00:00:00+00:00

4 | The Making of Sathima Bea Benjamin

Jazz . . . is what liberates you. It is the most liberating music on the planet.

âSathima Bea Benjamin, interview, Jazz Weekly

In the era of decolonization, when much of the black world saw Africa as the beacon of hope for the future of humanity, honoring and embracing African cultures underscored the continentâs arrival on the world stage. For African Americans, especially, identification with Africa and the Third World transformed a minority struggling for basic civil rights to a world majority demanding human rights for all formerly colonized and oppressed people. The journeys of Guy Warren, Randy Weston, and Ahmed Abdul-Malik reveal that the elements of indigenous culture they celebrated were not always ancient and traditional but new and modernâhighlife being perhaps the best example.

But as most of the continent celebrated political independence, in South Africa the white minorityâruled racial state tightened its grip. In 1948, the predominantly Afrikaner National Party came to power and immediately implemented legislation intended to weaken multiracial struggles for social democracy, labor rights, and racial equality. The apartheid laws, as they came to be known, further codified racial segregation and severely limited rights of nonwhites in South Africa. The laws prohibited marriage and sexual relations across the color line; classified the entire population by four âracialâ categories of Bantu (Native), Asian, Coloured, and White; divided residential rural and urban areas strictly by race; segregated public accommodations; barred black workers from striking; and essentially outlawed every liberal antiracist organization under the guise of anticommunism. The Bantu Education Act (1953), passed a year before the U.S. Supreme Court declared âseparate but equalâ education unconstitutional, created a draconian, state-run education system based on the principle of separate and unequal. The apartheid state imposed a national curriculum for Africans allegedly suited to their status as a permanent cheap labor force. All these restrictions were enacted under the guise of preserving âtraditionalâ cultures. Science and anything but the most remedial math were prohibited, and the social science curriculum promoted white supremacy and nonwhite inferiority. The act was just one example of the apartheid regimeâs twisted deployment of âtraditional cultureâ as a weapon to subjugate Africans. There was no room for âNativesâ in modern South Africa, except as maids, cooks, and laborers. In this severely segregated context, something modern and international, like jazz, was considered anathema by the apartheid state. To South Africaâs black and âColouredâ population, however, modern jazz potentially embodied an inherent critique of apartheidâs racial illogic. As mass opposition to the regime grew during the 1950s, jazz served as one of the prevailing soundtracks of struggle.

This social and political cauldron produced some of South Africaâs greatest musical figures, notably Miriam Makeba, Hugh Masekela, Chris McGregor, Letta Mbulu, and Abdullah Ibrahim. And it was that same turmoil that caused them to flee their country. Whereas African American artists like Randy Weston sought freedom by traveling to Africa, generations of South African musicians sought freedom in escape, in exile. It often meant finding their

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Classical | Country & Folk |

| Heavy Metal | Jazz |

| Pop | Punk |

| Rap & Hip-Hop | Rhythm & Blues |

| Rock |

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31931)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31920)

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26586)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19023)

Plagued by Fire by Paul Hendrickson(17394)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(15901)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15312)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14041)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(13836)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13296)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12358)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8956)

Adultolescence by Gabbie Hanna(8904)

Note to Self by Connor Franta(7659)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7540)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7307)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6188)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5398)

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah(5361)